As outlined in the Overview of the Private Offering Process, when raising equity capital, one of the first things a company should do is prepare a business plan. Good business plans typically include a long-term capitalization strategy. The business plan often forms the centerpiece of the private placement memorandum (PPM), the disclosure document that is typically circulated to investors. When putting together a PPM, the goal is to create both a complete synopsis of the company’s current situation and an accurate summary of the company’s plans for the future.

With a good business plan in hand, people preparing the PPM often turn to “due diligence” and corporate “clean up.” As it relates to private offerings, due diligence is the investigation that ensures that the company-related information and summaries included in the PPM are accurate and complete.

It is not uncommon that during the due diligence process, issues are uncovered that either should have been addressed earlier but weren’t or that need to be completed or addressed prior to the company issuing securities to outside investors. Remedying those items is often referred to as corporate clean up.

The Due Diligence Process

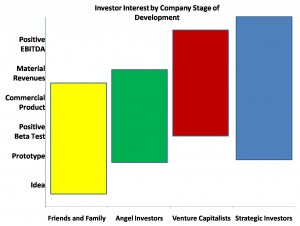

While the due diligence process conducted by venture capital firms is often more detailed than that conducted by angel investors, one should expect at least a base level of due diligence from both groups. Virtually all venture capital firms and most angel investor groups have a formal due diligence process in which they request in writing certain information and access to particular documentation. Here’s a sample put together for angel groups. According to a study sponsored by the Kauffman Foundation in 2007, the median duration of actual due diligence work conducted by angel investors in their large sample was roughly 20 hours per investment. Interestingly, the same study found that the those angel investor groups who spent more than the 20 hours had a 5.9x return on their investment, while those who spent less than the median 20 hours had only a 1.1x return. Regardless of the actual duration of the diligence conducted by groups you may work with, the point that is imperative to get your “house in order” before opening the company up to outside scrutiny.

As part of your disclosures in the PPM, it is essential to accurately summarize all “material” facts concerning the company. A fact is material if a reasonable investor would consider it important in determining whether to purchase the securities that the company is selling. In other words, you need to include all relevant facts that an investor might consider important in making his or her investment decision.

The due diligence process for an individual company should be designed to capture those material facts. The areas that are subject to the due diligence investigation vary from company to company, but often include the following:

- Organizational documents (e.g., charter documents)

- Cap Table and Shareholder and option/warrant holder lists

- Copies of agreements that affect equity holders (e.g., shareholder agreements, voting agreements, investor rights agreements)

- Financial statements

- Summaries of litigation or threatened litigation

- Governmental licenses and filings (including patent applications)

- Biographical summaries of officers and directors

- Material contracts

- Any conflict of interest transactions or arrangements involving the company and its current owners (including their affiliates)

The PPM should include summaries and descriptions of not only the items listed above and the business plan, but also anything else that may be material to a prospective investor’s investment decision.

Government agencies (such as the NASD) have frequently commented that there can be no definitive list of items to be described in the disclosure documents. For example, a company that is seeking funding to support clinical trials should likely also include a summary of additional funding that the company will need after the current financing in order to get the drug or product through all phases of the clinical trials. A software company that is reliant on the adoption of certain third party technologies probably should include details about that technology. In essence, every company is different and each due diligence process must be customized based on the nature of the offering and peculiarities of the company and the industry in which it operates.

Conducting corporate clean-up

Early-stage companies typically spend much of their financial and human resources on product or technology development and attracting and retaining talent. Whether it is because of lack of time, money, or experience, companies often fail to keep up with many tasks that may prove to be important to the success of the company.

What usually occurs is that during the due diligence process, areas that need clean up are revealed. If you think your company is good shape, consider these questions:

- Have your key employees signed appropriate nondisclosure, assignment of inventions, and noncompete agreements?

- Have you granted stock options or issued restricted stock to your key employees (perhaps as previously promised or alluded to) and if so, have you complied with the tax code section 409A requirements on valuations?

- Are your shareholder and director meeting minutes up to date and in compliance with statutory and organizational document requirements?

- Have all previous stock issuances and significant agreements been properly authorized in the board meeting minutes?

- Have you filed applicable patent applications (or at least provisional patent applications)?

- Do you have any agreements or arrangements with others that should be reduced to writing?

These and other matters need to be remedied or addressed before the private offering.

The other form of corporate clean-up prepares the company for its planned structure following the financing. For example, a company’s articles of incorporation and bylaws may need to be amended to reflect changes from the company being owned and run by a small group of founders to one in which there will be a significant number of outside investors. This is especially true if you plan to offer a type of security in the private offering that has not been previously authorized (such as a new series of preferred stock).

Also, sometimes a company will try to complete certain transactions or enter into agreements with one or more “household-name” companies in order to validate the company’s product or technology prior to the offering.

Conducting a thorough due diligence and corporate clean up are essential when offering securities. Doing both creates the foundation for a solid PPM: one that both provides a prospective investor with an accurate picture of the company and limits the liability exposure of the company and its officers and directors.